DeepSync (An NMA Project)

Neuromatch Academy (NMA) is a 3 week long, 120+ hour bootcamp aimed at introducing the Neuroscience community to Deep Learning and Computational Neuroscience via applied learning. In addition to learning content, we worked on a project throughout the duration of the bootcamp that was presented to other students, TAs, mentors, and even (in some cases) sponsors. I participated in the Deep Learning Bootcamp this August where a group of 3 of us (Daniel Brown, Malcolm Udeozor, and me, Satvik Mojnidar) worked on a model to classify seizures in patients with epilepsy.

The Problem:

Epilepsy is a large set of disorders resulting in debilitating seizures. According to the Epilepsy Foundation, “Epilepsy is a spectrum condition with a wide range of seizure types and control that varies from person to person.” Some epileptic seizures are triggered by specific events and others can occur at any point in time, regardless of activity. Because of this high variability, it is often hard for patients, nurses, or close friends/family to predict them. If a patient is in a vulnerable situation such as driving, a non-fatal seizure can indirectly become fatal. Maintaining a fulfilling life can be a challenge for people with epilepsy. Our goal was to see if we could predict seizures from a dataset provided by Epilepsy Ecosystem, an organization aimed at maintaining a database of epilepsy recordings for researchers.

The Dataset:

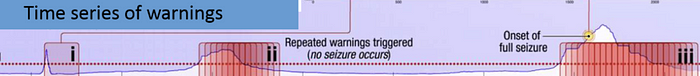

Our dataset was part of the Melbourne AES/Mathworks/NIH Seizure Prediction Kaggle competition held from 2015–2017. It consists of hundreds of 400hz iEEG recordings from 3 epilepsy patients. Each recording is 1 hour in duration and either was in between seizures (interictal) or resulted in a seizure (preictal). There were no seizures resulting from an interictal recording, hence the label in “between seizures”. The recordings stopped 5 minutes before the seizure took place. This was because the task was to predict a seizure before onset, rather than recognize a seizure during onset. Therefore, our model was made to predict a seizure at least 5 minutes before it occurred. The recordings were then split into 10-minute segments, 6 per recording, and each binarily labeled to indicate whether or not a seizure occurred. Each iEEG recording was made up of 16 electrodes spread out over the cortex.

All 16 electrodes were:

- recorded simultaneously for one hour

- split up into 10 minute .mat files

- labeled as interictal or preictal (0 or 1)

Of our testing set, 30% was given to us and 70% was kept by the organizers for further testing. This was done to ensure that no group would reverse engineer a model to perform well only on the testing data.

The Plan:

We were a motley crew who only had one thing in common — neuroscience. Dan had just finished his neuro masters in Norway and was heading back to the United States for his Ph.D., Malcolm was a pre-med neuro post-Bacc doing research at the NIH, and I was a rising senior neuro major/computer science minor at UT Austin. None of us were necessarily experts in Data Science, Machine Learning, or even Computer Science.

So how could we solve this problem, let alone in three weeks?

Our first step was to do some research. After hitting the books, looking at our dataset’s documentation, other teams’ past experiences, and general scientific literature on the subject matter, two things were clear:

- We might not have enough data to build a Deep Learning Model from scratch

- Training a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) might not be realistic for a 3-week timeframe

In total, we had around 150GB of training data available. That might sound like a lot, but it’s important to note that these segments have a sampling rate of 400hz, and each file is 10 minutes long. That means that at each second there are 400 samples, and there are 600 seconds in the dataset — in total 240,000 data points per recording electrode. This means that the bulk of the memory lies within each segment, rather than between electrodes, segments, and patients.

Why does this matter?

A deep learning model like ours benefits from a large number of labeled data entries, not the length of each data entry. We didn’t have many data entries, but each entry was very large in memory.

That leads us to the second problem — creating, training, and fine-tuning an RNN in under 3 weeks. Recurrent Neural Networks are used to model sequences by maintaining a memory of a past entry to predict the next. RNN’s are a go-to for beginners looking to create a model for sequential data like a time series, or, in our case, iEEG recordings. What makes an RNN hard to train is that same reliance on recurrence. Because each prediction relies on the previous prediction in the sequence, data can no longer be loaded into our network at once. This sequential processing not only takes longer but also is prone to error through vanishing gradients. While there have long been solutions like LSTM/GRU’s or transformers, we thought there might be a simpler strategy: Power Spectrum Density Energy Diagrams (PSDED).

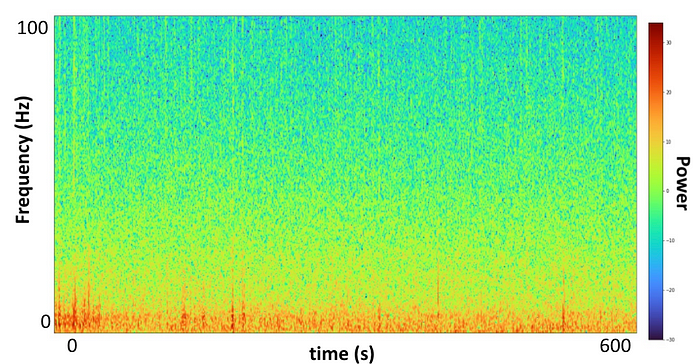

These diagrams are colorful images describing an entire time series in one image. Our 10-minute segments of 16 electrode recordings of 240,000 data points were now represented in 16 images, one for each electrode. Through Welch’s method (SciPy) we were able to plot frequency as a function of time on the spectrum of power. Now all 16 sets of 240,000 data points, each 10-minute recording, were represented on a set of 16 images. What if we input these diagrams, which fully describe our data within a single image, rather than a data frame of 240,000 data points?

After further research, we found a paper that did just that, implementing transfer learning of well-trained CNN’s to classify seizures through PSD diagrams. Transfer learning is the practice of taking a pretrained network, usually one trained on massive crowdsourced datasets, and fine-tuning the network to work on a new, similar but distinct dataset. This solved both our problems. We no longer needed a massive amount of data (because we’re using a network that’s already been trained on the basics of denoting lines, colors, and orientations) and we no longer needed to train an RNN; we could just use a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). CNN’s are built to process images by assigning color values along a spectrum (I.E. Black/White or RGB) and determining which are the most relevant in order to recognize specific subjects or orientations. It was time to try it out ourselves. We decided to use Inception-ResNet V2 trained on Imagenet, as it performed best in our reference paper. Inception-ResNet V2 combined the efficiency-in-depth of the Inception networks with the residual connections of the original ResNet. Read more about it here.

We changed the input layer to take in 16 images on RGB channels (48 total channels inputted) and the classification layer to classify interictal (0)or preictal (1). In order to stop overfitting because of our small dataset, all layers except the two modified layers had frozen weights. Finally, to keep things simple, we used an Adam optimizer and Cross-Entropy Loss.

Because of time constraints, we could only train it on 1/3 of our first patient’s data. This means that our network is not working at full potential just yet, but all we wanted to do for now was a proof-of-concept.

The Results:

Our first goal was to overfit a small portion of our data on our model to prove that this was, in fact, a viable approach to classifying seizures; after all, if a model can’t memorize the training data there is no way it will be able to predict the testing data. After performing an overfitting of 24 training samples and 8 validation samples, we achieved a validation accuracy of 75%. This means that after overfitting the training data completely (100% prediction accuracy) we were able to then use the trained model to predict 6/8 validation samples. That was great for us! The next step was to train it on the next batch of data we had: 1/3 of Patient 1. After training on 156 samples we tested on the 30% of data that was given to us by the competition organizers. There we were able to get a 66% accuracy on testing. That was big news to us, because after only training on 1/3 of our Patient 1 data, we were able to achieve a 66% accuracy on the entire Patient 1 testing set.

The Aftermath:

Did we hit our goals? Yes! We were able to create a model that learned to predict seizures greater than random chance (50%) through CNN’s and transfer learning. Did we get a high enough accuracy to place on the leaderboards of the Kaggle competition? Well, we’re not done yet. We only trained on 1/3 of Patient 1 data. That’s 1/9th of our total data. Training our model on the rest of our data would likely yield better results on the testing set by improving generalizability. On top of that, when preprocessing, we omitted recordings that contained more than 50% “data dropout” which is an unexplained phenomenon consistent along all recording electrodes resulting in a loss of data for a specific time period. Our dropouts ranged from only a couple of seconds to the entire 10-minute recording. Dropout is represented as large empty white bars in our images, which can contribute more noise when predicting through a CNN than if we used normal time series strategies (RNN’s etc). Addressing dropout could make a big difference in improving our accuracy. One strategy to reduce extreme noise is to impute the missing data. Imputation is replacing missing values in a time series with a random sample or average of a recent previous segment. Imputation works well for small instances of dropout but loses credibility for larger intervals, our challenge will be to figure out when imputation is necessary and when throwing out the recording altogether is required.

At the start of NMA, we were three neuroscience students with minimal experience in Deep Learning. By the end of NMA, we had created a model to classify seizures through a novel approach. Not bad for three weeks! Stay tuned for our results on the entire dataset, and in the meantime, check out this cool paper I recently stumbled upon detailing Neuropace’s attempt at classifying seizures through PSDED’s as well.

Thanks to our TA Jasleen Dhillon, Project Mentor Lucas Tavares, and pod mates from the Mighty Antelopes for their invaluable advice over the course of NMA!